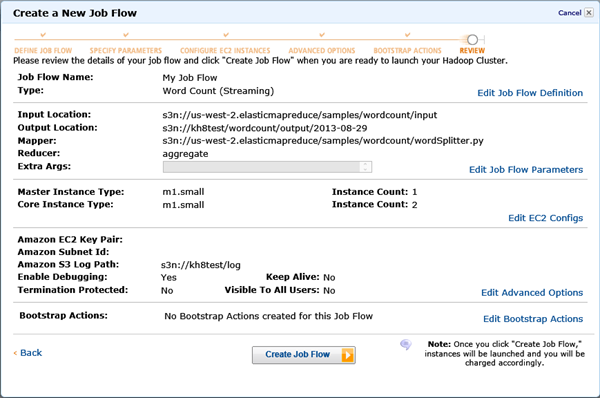

This is a 1-page basic guide to data protection law, particularly relevant to open data / big data in cases where the data processed involve 'personal data'.

Data protection law in a nutshell

To tech folk, 'data protection' usually means IT security. To lawyers, 'data protection' usually means data protection laws. There's some overlap, but they're not the same. I'm just going to use 'data protection' in the legal sense.

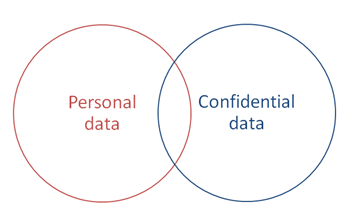

Data protection is also not the same as privacy. Again, there's some overlap, but technically they're different. Data protection laws can even apply to public data, ie non-private personal data. Privacy law in the UK has largely been developed by the courts under Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights to protect people against the misuse of their private information (mostly, celebs who can afford to litigate).

There are also laws about the use of confidential information, which could cover some corporate commercial data:

Data protection laws are really broad because 'processing' is almost anything you can do with or to personal data where it's been digitised at some point in the process, including just storing, transmitting or disclosing personal data as well as actively working on it. And 'personal data' is basically anything that can be linked to an identified or identifiable living individual ('data subject'), so something that's not 'personal data' one minute could become 'personal data' the next if it's become linked to an identifiable person through big data crunching, for instance.

Data protection law requires 'controllers', ie anyone who controls the 'purposes and means' of processing personal data, to process personal data according to certain key principles (regarding not only the use or abuse of personal data but also issues such as data accuracy and security), with tighter rules for certain sensitive information like health-related data. Failure to do so may be punished, mainly by the regulator (who in serious cases can fine up to £500k in the UK), or in some very limited cases the affected data subjects could try to stop the processing or sue for compensation. Breach of principles could also be a criminal offence in some situations. Controllers must register with or notify the national regulator and pay fees.

The concept of anonymous data is recognised. The approach taken is quite binary, in the sense that if something is 'personal data', all data protection law rules apply to it, so it must be processed in compliance with the principles etc; whereas if it's not 'personal data' but anonymous data, then none of them do. Of course in actuality the dividing line is harder to draw, but the law is what it is. Many laws are like this, claiming to apply to things in different ways depending on whether or not they fit within a set category or categories, implicitly assuming that there are bright lines between them, when in fact it's often hard to work out which if any category a real situation fits into, and technological, social and business developments can make the dividing lines even blurrier over time.

Something is not 'personal data' if it's been anonymised so that individuals can't be identified by any means 'likely reasonably' to be used to attempt de-anonymisation, including by combining it with other data (note: that refers to the means likely to be used, not the means actually used: if you can re-identify, eg because the anonymisation hasn't been done very well, the 'anonymous' data are still personal data even if you don't actually do it). This again means that as re-identification methods improve, something which used to be anonymous data could become 'personal data' when techniques get to the point that the data could be deanonymised. [Clarification: the 'likely reasonably' wording is from the EU Directive. For the UK-specific position and summaries of cases, see the Anonymisation Code of Practice]

EU data protection law comes from the Data Protection Directive. This applies to countries in the European Economic Area (I've done a Venn diagram showing the differences between EEA, EU, Europe and Council of Europe). As this is a Directive, not a Regulation, EEA countries have room to implement it differently, so detailed data protection laws may vary with the country - and do, sometimes significantly. For example, some countries protect the 'personal data' of organisations as well as people (the UK doesn't). The rules on security are about a few paragraphs long in the UK, several pages long in Italy.

The ICO is the UK's data protection (and freedom of information) regulator. It's published lots of useful info both for data subjects and for those who process personal data, so do rootle around its website.

I should also mention the Article 29 Working Party, the group of EU data protection regulators collectively. It's produced many opinions and other documentation, including on:

- open data and the reuse of public sector information

- purpose limitation including big data

- apps on smart devices eg smartphones, tablets

- cloud computing

- cookie consent exemptions

- biometrics

- facial recognition in online and mobile services

- geolocation

- RFID (with Annex)

- social networking

- search engines.

So there's lots of guidance out there, it's just that most people who aren't data protection specialists don't know about it (and, of course, may not know how to understand or apply it in practice).

But note that regulators' guides and opinions aren't legally binding - only a court case can provide definitive guidance. However, if you follow a regulator's guidance, you're of course less likely to find yourself in its enforcement sights.

General info

There's basic info on UK data protection law plus guide to data protection including:

- the 8 Data Protection Principles, which say that personal data must be:

- Fairly and lawfully processed

- Processed for limited purposes

- Adequate, relevant and not excessive

- Accurate and up to date

- Not kept for longer than is necessary

- Processed in line with data subject rights

- Secure (including the 'technical and organisational measures' mentioned in the first diagram above)

- Not transferred to other countries without adequate protection

Notes:- there are mnemonics for the principles

- that there are specific rules restricting automated decision taking regarding individuals eg use of credit scoring or other algorithms, which could include actions based on profiling people

- the need to register with the ICO (the list of registered organisations is public) and pay annual fees - if you should register, and don't, it's a criminal offence, and people have been prosecuted for not registering

- exemptions (like processing for personal domestic purposes only, or for law enforcement) - situations when you don't have to register, comply with the principles etc

- specific rules on direct marketing and yet more, guidance on separate rules on direct marketing too (direct marketing checklist), eg if a startup has a marketing mailing list

Remember that the ICO can take enforcement action for breaches (and has a policy on regulatory action). This can include imposing monetary penalties (framework, guide, procedures - and see what enforcement action it's taken so far including criminal prosecutions, and CSV of fines issued so far).

For organisations like startups

There's a checklist on data protection compliance, a checklist on collecting personal data, and a brief general guide for small businesses.

The ICO website has free training materials including videos and security guidance. You can ask the ICO for help, eg request an advisory visit to your organisation.

On privacy notices in particular, there are guides on:

- privacy notices code of practice

- checklist on privacy notices for startups / SMEs.

Note:- the mobile trade association MEF has just launched a free online privacy notice generator for apps, AppPrivacy, developed by a global working group. It's not necessarily enough by itself to ensure you're compliant under your own national laws, of course, but it's much better than having no privacy notice at all (here's a developer's experiences with testing it).

-

The ICO has sectoral guidance including for non-profits and the health sector, and you can see its full list of guidance material, including specific guidance on certain areas like:

- Anonymisation Code of Practice and Privacy Enhancing Technologies

- Data sharing

- Privacy impact assessments (PIA) before you launch a new product or service (this is a US example, but remember Google's record fine for its Safari tracking, which was said to break the promises it had made the US FTC after the Buzz fiasco? Conducting a PIA before either launch might have helped…)

- A new improved version of its guide to conducting a PIA is currently out for consultation, closes 5 Nov 2013.

- Processing personal data online including on use of cloud (it's not easy to comply with this in practice when using public cloud to process other people's personal data, mainly because of cloud providers' standard terms - see negotiating cloud contracts; summary)

- CCTV

- Crime mapping

Regarding sensors etc and the infamous cookie law:

- the cookie law is a separate law, and has to be complied with in addition to data protection laws

- the cookies law could apply to storage of or access to info in anything which is 'terminal equipment' (which might include sensors, smartwatches etc), even if no personal data are involved - ie even when accessing supposedly anonymous data. So cue more privacy notices….

- see cookie law in a nutshell (20 questions); also there's an ICO guide. (I've blogged quite a bit about the cookie law, mainly about websites, but including links and free cookie law tools and cookie law humour!)

To keep up to date - the ICO has:

For data subjects (whose data are being processed)

You have some data protection law rights, here's info on two main ones:

- How to request your personal data from the organisation that's processing it (you can be charged £10 or more, depending).

- Note, this is not the same as requesting info from a public authority under freedom of information laws (there's FOI guidance too). They're meant to be mutually exclusive: you can't request personal data under FOI.

- How to stop an organisation processing your personal data (the rights are much more restricted than you might hope).

You can complain to the ICO, for free:

- General info about complaints

- Assistance with complaints including a helpline

- FAQs on rights and complaints.

You could also sue for compensation in some situations but they're very limited, as you can tell from that link being directed at organisations and the lack of similar general info for individuals about suing! And you'd have to get lawyers to help you litigate. You could try to DIY, but that didn't work out very well for Mr Smeaton (short summary (scroll down), longer summary, another summary, full judgment).

However, an eminent data protection expert has argued that even the non-rich could, instead of suing, try complaining about privacy breaches (not just data protection breaches) to the ICO, ie 'ask [the ICO] for an assessment with respect to lawful processing with respect of Article 8' - and I think he's got a point there. So if you try this, good luck and please keep me informed!

"We can't, because of data protection"

Let's just dispel one myth. Too many organisations hide behind 'data protection' to refuse to do something that they can and indeed should do. Maybe because they just don't want to, or couldn't be bothered, or they're covering themselves and think it's just easier and safer not to do it. And they often get away with this, because too many people don't understand data protection law and believe their 'It's data protection' excuse.

That's partly the fault of data protection law and regulators, because the law is very complex and detailed, and there's tons of legislation and guidance to wade through (as well as some cases interpreting the law). But the basic principles are mostly quite straightforward (listed earlier).

The ICO has tried hard to address these practices by organisations, which it calls 'data protection duck outs' (eg myths and realities about data protection), but believe it or not there have been 'data protection' incidents regarding animals, trees and kids (plus a Superman suit). There are also myths about data sharing, and myths about marketing calls too.

Occurrences like this don't exactly fill one with confidence that things may change for the better. We can only hope that more people will learn about these myth debunkers, and that bureaucratic organisations will start applying common sense and stop using 'data protection' as a justification for introducing more unnecessary 'get in the way' red tape.

Usual weaselly disclaimers (and why you should use lawyers, and where to get free legal advice)

May I stress that all the above is general info only, not legal advice!

Lawyers say this sort of thing because legal advice needs to be tailored to your individual situation, and inevitably everyone's is different.

Also, laws don't always mean what they literally say. We'd love them to (as would the Good Law initiative), but sometimes, maybe even often, they don't. This may be because there can be layers of meaning, or qualifications, conditions and/or exceptions, so that it's sometimes necessary to wade through provision after provision, following the trail of definitions through to still further legislation, before it's possible to get even the bare bones of what something means.

For instance, 'fair and lawful' in the first principle means more than just 'fair and lawful': for processing to be 'fair and lawful', it must first fit within one of several defined boxes ('consent' is one), and it also has to be generally fair and lawful. And I've put quotes around 'consent' because 'consent' itself has a specific meaning, it's not 'consent' unless the consent was a freely-given, specific and informed indication of the data subject's agreement to their data being processed.

Or, legislation can be drafted obscurely, so it's hard to figure out what it means, and it would take a court case to find out what judges think it means. Or, legislation can be drafted by people who don't understand how technology works (yes it happens!), whether it's websites, or cloud computing. Or, the legislation is so old that it didn't properly envisage future technological developments - like copyright law controlling the right to copy rather than the right to use (book), leading to effectively all computer usage being copyright infringement because the technology works by copying. It's often hard to apply old or unsuitable laws to modern technology.

Even when an issue has gone to the courts for decision, while some judges are admirably easy to understand, with others even seasoned lawyers may get even wrinklier-browed desperately trying to figure out exactly what m'lud meant. Sometimes, it's because the judge isn't as clear as he or she could be. Other times, it's because judges are trying to do what they feel is the fair and right thing, and so may suggest or say that the law means something other than you might think it means (I dub this the Denning dimension, aka 'The little old lady wins!', sometimes manifested as 'hard cases make bad law'). That's why, while technologists may think in binary, in either/or, lawyers have to think in analogue - in shades of grey:

(Image reproduced by kind permission of Firebox.com)

And that's also why attempts to translate laws into algorithms and code are almost certainly doomed to failure; it's near impossible, as for example an experiment in implementing supposedly simple road traffic rules in software showed.

Lawyers with expertise in particular fields, whether data protection, intellectual property or computer law, have been trained to understand the jargon and to know or be able to work out how to reconcile all these different elements in order to determine what the workable paramenters are, and to arrive at something that can make some kind of sense in practice.

In addition, experienced practitioners should have a feel for how the law is actually enforced in real life, eg by regulators, so that they can give you some idea of how likely it is that you'll be fined or worse, and what the penalties are. Then you can decide, particularly in the (too many) areas where the law isn't clear, whether to take the risk that (a) whatever you plan to do. that might be a breach, will be found out, (b) authorities will take enforcement action against you, and (c) you'll be fined or prosecuted for it.

Of course, if you use lawyers rather than DIY, you might be able to sue them if things go wrong and it's their fault - because practising lawyers should be insured!

Finally, the internet may be global but laws are national, so different countries' laws may apply in different (or indeed the same) situations, and so you may need advice from lawyers qualified in the relevant countries.

Therefore, at some point a startup will need a lawyer. Not just to keep certain lawyers (alas not me) in mansions and private school tuition fees, but for its own benefit in terms of protecting its IP, making sure it's not breaking data protection or other laws, and certainly when it comes to that hoped-for cashing-in IPO.

Law centres, citizens advice bureaux and the Bar pro bono unit are free, but may lack specialist IT or data protection expertise. Own-IT can give free intellectual property law advice, and Queen Mary, University of London (where I'm a PhD student and working part-time) has an advice service including a Law for the Arts Centre that offers free IP law advice, but again may not necessarily have IT or data protection expertise. However, Queen Mary is also launching a new free advisory service for startups, qLegal, aimed at providing legal and regulatory advice specifically to ICT startups, where postgrad students will work with collaborating law firms and academics - so please feel free to try that!

Disclaimer: the book I linked to above is by my PhD supervisor, but I linked to it because it makes very salient points on why many laws don't work in cyberspace and how they could be made work, plus it's a good read (even for non-lawyers) - not because I'm trying to curry favour!